Tl;dr: money has four functions within society: it is a value indicator; value itself; a facilitator of exchange; a wealth redistributor.

In this article, we take a look at the nature of money, where it came from, how it works, why some people have it, and why others don’t.

Table of Content

- Pre-Origin Times

- The Hermit Is No Longer…a Hermit

- The Emergence of the “Law”

- Cooperation

- The Specialization of Society

- Bartering

- So…What Is Money?

- The Third Function of Money

- Money Traps

- The Wealth of Nations

- The Fourth Function of Money

- Why Capitalist Societies Are Richer Than Communist Societies

- The Bottom Line

What Is Money, How It Works, and Why We Need It

Pre-Origin Times

I like to think that the need for money is associated with the need for law.

Both of these human-made concepts appear once a society with only one person (uni-individual society) evolves into a society with several people.

Let’s take an example.

Imagine a hermit on an island. The hermit lives alone.

He built his house by himself, feeds himself by himself, dresses by himself, and entertains himself…by himself.

Does money exist? Obviously not: there is no one to buy from or sell to.

The hermit finds the needed resources in his environment, which is “free” (minimum work must be done to extract resources.)

The hermit’s society is utopian: there is no crime because there is no law (and alternatively, no one to kill or steal from).

There is no authoritarianism because there is no one to confiscate freedom. By the same token, the inherent condition of our hermit is freedom, because there is no one to take it away from him.

There is no poverty because the hermit can’t afford to be poor. Poverty would mean death, as there is no one to save the hermit.

The hermit “lives”, and is accountable to himself for his own survival.

Notice the amount of control the hermit exercises on his environment.

If he decorates his house in such a way, no one will come to change it. If he sorts out his clothes in such a way, no one will move them either.

Whatever the hermit controls in his environment is controlled by him and him alone.

The hermit control 100% of what can be controlled.

This notion is important. It underlines how the massive system we created called “society” is a consequence of interactions between individuals.

If as little as one person joins our hermit, the whole society changes.

The Hermit Is No Longer…a Hermit

The addition of one person to the hermit’s island changes everything.

Alone, the hermit had full control over his environment, as we said.

When a new person joins him, the hermit loses full ownership of control and must now share it with the new person.

Furthermore, the existence of a new individual adds elements of randomness to society. The new person cannot be entirely controlled like a pet could, for example.

What was formerly under the direct control of the hermit (how he decorates his house) isn’t anymore. He has to share control with that new person.

In order to get along, these two will have to agree on some rules: the Law.

The Emergence of the “Law”

L’enfer, c’est les autres.

Now that the hermit is no longer alone, he can interact with someone else.

Since the hermit and the new individual are two different people, and that the possibilities of environmental control are limitless, they will first have to create an agreement on the ownership and percentage of control of the controllable variables.

What does that mean? It means we need a code of conduct to say who does what and how.

That’s basically the definition of the “law”.

Humans, when alone, exercise 100% of control upon the controllable variables of their environment.

In the presence of other people, the control of what is controllable must be shared, which results in a loss of ownership, hence weaker control.

To sum it up, when society evolves from 1 individual to 2 individuals, the original individual’s control ownership decreases as the new person adds elements of uncontrolled randomness into the environment and possibilities of control of that which was previously controlled by the initial individual.

From a control point of view, the hermit loses it all.

But from a “possibilities” point of view, the hermit makes substantial gains due to the possibility for cooperation.

Whatever the hermit lost in control, he gained in productivity thanks to the appearance of a new principle: cooperation.

Cooperation

While “other people” decrease the amount of control you have over your life, they also give you the chance to cooperate.

When you do, you achieve work bigger than the sum of its part, a concept absent in the uni-individual society.

As a result, the share of control you give up on the island is widely compensated by cooperation.

Why is cooperation important?

Because it enables the hermit to become more productive. Trees that used to be impossible to carry, can now be carried.

The coconut that was impossible to be picked up, can now be picked up.

While the number of people on the island has been multiplied by two, the productive output has been multiplied by three.

As my dad used to say, “working in duo triples the output for equivalent time and efforts”.

He wasn’t wrong.

The incremental added-value from 1 person to 2 people is important.

Let’s do some math:

1 person produces 1 unit of output → 1 person = 1 unit

2 people produce 3 units of output → 1 person = 1.5 unit

→ total productivity multiplier for one person added= 300% (from 1 unit to 3).

Of course, we need to keep in mind that while the hermit now produces more coconuts, he will also have to share them with the new person. However, they will both have more coconuts than when the hermit was alone.

Did the hermit gain something by welcoming that other person on his island?

Mathematically, yes. He gained more coconuts.

He is now more productive and can enjoy more wealth than before, provided the loss of control on his environment is estimated to “be worth less” than the new volume of coconuts he has. .

Will a newly added person always multiply the total produced coconuts by 300%?

Hell no.

The biggest incremental gains happen when a society transitions from 1 to 2 people.

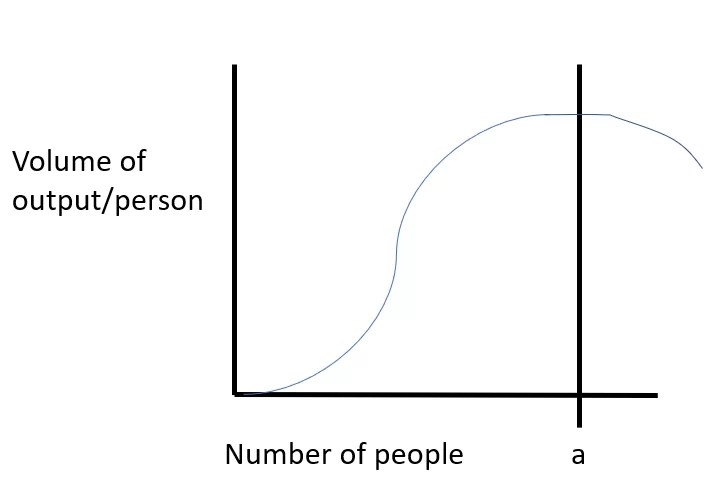

However, more people will mean more coconuts, and more coconuts per person (output/person), until you reach the efficient societal size (roughly 150 people), where one added person would decrease the volume of coconut per person.

This relation is expressed as follow.

Ideally, a society would stop adding people when it reaches point a.

I believe this graph explains why smaller societies have fewer social-economic inequalities than bigger societies.

The Specialization of Society

“So, what about money?” I’m getting there.

As society grows, it specializes. When the hermit lived alone, he’d do everything himself: cleaning, cooking, walking the dog.

Now that one person joined him, they got into an agreement that makes them both more productive.

The hermit now fishes for two while his wife gardens.

The incremental effort between fishing for one and fishing for two being minimal, this agreement helps our two inhabitants cooperate which makes them more productive.

Indeed, the hermit won’t eat fish for two, and his wife won’t only eat the apples and pears from the garden.

The hermit will exchange fish for pears, and his wife will exchange pears for fish.

This system is called bartering, and it is believed to have taken place before the invention of money.

Bartering

Bartering is an exchange of value between two or more people.

To be fulfilled, bartering must meet four conditions: (a) agent A owns something that (b) agent B wants and (c) agent B owns something that (d) agent A wants.

Needless to say that four conditions are a lot of conditions.

What if agent A has something that B wants but A doesn’t want what agent B has? It wouldn’t work then.

In this case, the two people can’t barter.

This is where money gets into play.

What if they had some sort of mediator in between goods owned by A and goods owned by B? Some sort of neutral value that could be exchanged against anything else?

In this way, if B had something that A didn’t want, this neutral value could be exchanged instead. This way, A wouldn’t have to get unwanted goods from B.

And that’s how money came to be.

So…What Is Money?

Here’s the best definition I could come up with.

Money eases the exchange of goods and services between agents by defining a value of the exchanged good or service that both parties agree on at instant t.

However, money does not only define the value of the traded goods. It also embodies that value since it is exchanged against the good.

We could say that money embodies both some sort of scale and the unit that makes up the scale, a bit like if “degree” and “thermometer” were the same thing.

Money is therefore both an assessor of value and the value itself (first and second characteristic).

-> 5 euros is as valuable as 5 euros, and can be exchanged against anything worth 5 euros.

The Third Function of Money

Let’s summarize: when a society is inhabited by several people, these people interact with each other by exchanging goods and services whose worth is measured by and exchanged against money.

Money being highly liquid (easily exchangeable), it can be traded against anything else, which is the main reason for its attractiveness → money is an enabler (“simplificator”) of trade (third characteristic).

As we explained above, money does not only represent value, but it is also a way for people to trade and produce a good or service for others.

We can therefore reasonably conclude that people will give you money if you can give them something of value in exchange.

A diamond will be sold for a lot of money because its value is very high.

A random rock will not be sold for much (unless it’s an NFT ;)).

As such, the basic original assumption is that:

Money = value at instant t

The surgeon makes a lot of money because she saves lives and lives…are valuable.

The legal tax evasion lawyer makes a lot of money because he helps save a lot of money.

Actors make a lot of money because they entertain millions of people. Million = a lot of total value = a lot of money.

Bill Gates made a lot of money because he enabled billions of people to use a computer.

I make almost no money because I provide almost no value.

If you want to make a lot of money, you need to provide society with a lot of value.

And avoiding traps.