Takeaway

- We’re paying four times more taxes today in real terms than we did 50 years ago.

- The rich are widely supporting the tax system in developed countries.

- The tax system costs a lot of money, which spurs the rise of more taxes

- It’s likely that decreasing taxes would increase state revenue due to an increase in economic activity and a decrease in tax evasion.

- High taxes often trigger revolutions (US, India, Tunisia).

- One of the oldest written documents we have found was tax records.

- Taxes were invented before money.

- The best tax system is the one that minimizes the excess burden of taxation by spreading tax wide across different industries.

What Taxation: A Very Short Introduction Talks About

Taxation: A Very Short Introduction was written by Stephen Smith, a professor of economics at the University College London. The book gives a brief history of taxation and explains how taxes work in most developed countries, who pay the most taxes, how taxes impact the economy, and different issues about tax policy.

It’s a great book I wish many people would read as it accurately describes the infernal money-eating machine that modern states have become.

Consider that we have never paid as much taxes as we do now, and the situation has never been worst, which prompts people that don’t read anything to demand that we “tAx thE riCh”.

This book is great as it cuts through ideology to present a science-based approach to taxes.

Highly recommended.

9/10.

Table of Contents

Summary of Taxation: A Very Short Introduction Written by Stephen Smith

Introduction

Taxation is crucial to the functioning of the modern state.

Tax pays for infrastructures, the justice system, welfare, education, etc. The US levies 25% of its GDP in taxes and EU member states levy 40%.

On the other hand, taxes reduce people’s income and incentivize the usage of ways to decrease them as much as possible – up to shopping in other countries.

Taxation can have big consequences and trigger revolutions as it did in the US or India. This is why it’s important to understand them well.

Chapter 1: Why Do We Have Taxes

Taxes are compulsory payments, exacted by the state, that do not confer any direct individual entitlement to specific goods or services in return.

- Taxation is mandatory -> it is different than everything else in democracies because it is mandatory, while people often have the choice to do things -> likely why taxes get so much hostility.

- Taxation is parametric -> defined in the law. It wasn’t always this way in the past when many taxes were arbitrary.

Taxation isn’t new and has been existing for millennia.

In fact, one of the oldest documents ever written (in 3300 BC) are tax records. The need to record tax payments may have been the driving force for the development of writing.

In the beginning, taxes were paid in produced stuff (food, material, etc) or in labor as money did not yet exist.

Receiving taxes spawned the creation of a bureaucracy. A Mesopotamian expression said that “the tax collector was the person one should fear the most!”

A more modern form of taxes appeared in Greece and Rome as levies over the sale of certain goods (land, slaves, imported goods, etc).

The Republic did not levy tax by itself, but auctioned the right to levy taxes to private contractors. This was in fact a widely corrupted system that helped these contractors enrich themselves.

Then Augustus, aware of the problem, changed the system and established a property tax and a poll tax (a tax levied on everyone).

This led to the creation of a land registry to know who owned what -> City councils became tax collectors.

Some say the fall of the Roman Empire was due to ever-increasing taxes caused by:

- Rising costs due to military threats

- Declining revenue because the taxes were so high that nobody did anything anymore

Mobility was even restricted to prevent people from going to a low-tax jurisdiction.

When the Empire ended, taxes were simplified again like tithes (income tax for the Church) or forced labor (serfdom).

More modern taxes slowly reappeared even though kings did not hesitate to impose arbitrary taxes to finance their projects, military or else.

People slowly got sick of paying arbitrary taxes and it became a democratic issue.

The economic boom of the 19th and 20th centuries complexified everything, taxes included.

At the end of the 19th century, tax revenue was less than 10 percent of the GDP in the UK and France, and only seven percent of the GDP in the United States.

Then these countries suddenly started growing their public sector and demanded more taxes to pay for that.

Then the world wars came, and the state needed more taxes for that.

Taxes have exploded ever since.

Over the OECD area as a whole, taxation accounted for 25 percent of GDP in 1965, and 34 percent in 2012

The government’s taxing of its people has grown fourfold in real terms since the beginning of the 20th century, but it also developed important social services.

Chapter 2: The Structure of Taxation

The tax structure varies across countries, but all share common elements:

- Corporate tax

- Income tax

- Sales tax (VAT)

The rest differs from country to country.

Tax systems today are the result of a long evolution resulting from trial and error and the political life of the country.

In the OECD:

- Personal income tax represents roughly 25% of all taxes

- Social security taxes represent 25%

- VAT represents 20%

- Corporate taxes represent 10%

The most striking observation when comparing the evolution of taxes is that not only are we more taxed now than we were, but GDP also increased – which resulted in a massive budget increase for the government.

As a reminder, the volume of tax that the government is now levying increased fourfold in real terms since the beginning of the 20th century.

Some countries make more off their VAT, others of their personal income tax.

No one really knows what explains these differences besides that “it’s how things turned out to be”.

1. Income Tax

Income taxes today are the main taxes in most OECD countries, which may seem surprising since they were introduced late – at the end of the 18th century in the UK to fight Napoleonic wars before being abolished and reestablished in 1842.

2. Sales Tax (VAT)

Sales tax in the US is the VAT in Europe: Valued Added Tax.

These are taxes on spending covering all items with excise duties or higher additional taxes on things like alcohol, petrol, or cigarettes. They’re usually levied at the producer to avoid tax evasion.

High VAT taxes often incentivize the development of a black market.

VAT is paid by everyone but can be offset by businesses big enough to be subject to it.

Eg: if a company buys a computer, it will pay the VAT then will apply for being refunded the VAT.

3. Taxes Companies Pay

And then there are all of the taxes that businesses pay – over 90% of all of the taxes in the UK!

-> businesses contribute significantly to taxes! They pay taxes on salary, social security, then corporate taxes too.

-> businesses are used as “unpaid” tax collectors.

4. Other Taxes

- Transfer or ownership of financial assets and physical property (often the oldest in a tax system)

- Wealth and inheritance

- Use of natural resources and environmental damage

- International trade

- Miscellaneous fees, licenses, and permits

Chapter 3: Who Bears the Tax Burden?

To answer this question, we need to understand the difference in the notion of formal and effective incidence of tax.

Eg: the VAT may be imposed on sellers (formal), but it’s buyers (effective) that bear the cost of it.

If you want to understand who really pays, you need to ask: Whose living standard falls as a result of the tax?

In free markets, the tax impacts supply and demand. Taxing the buyer or the seller doesn’t actually impact the buyer or the seller – it impacts both.

The extent to which it impacts one or the other depends on the demand curve.

If taxes are imposed on the sale of goods where the price influences a lot whether people spend on it or not, then the cost of the tax will be borne by the producer (and the other way around).

- Taxes on wages:

- Borne by workers when they’re men (men work regardless of how much they’re taxed).

- Borne by employers when workers are women or old (women and old people work less when they’re taxed more).

- Taxes on land: land is in fixed supply, so it falls on the seller.

- VAT taxes: borne by customers.

- Taxes on business: the incidence falls on everyone except the business (mostly borne by the employees through reduced wages).

-> in the end, the burden of taxes almost always ends up on the employee/consumer.

The burden of taxes is important to understand for two reasons.

- Efficient taxes may end up mainly on poorer households.

- Politicians need to know if their voters will be impacted.

There are two types of income tax:

- Progressive: increases as the amount of money earned increases.

- Regressive: decreases as the amount of money earned increases.

The system used in modern states is progressive as countries strive to impose a low tax burden on poorer households.

Indirect VS direct taxes:

- Income taxes are direct taxes and it’s easy to make “the rich” pay with them.

- VAT are indirect taxes.

Indirect taxes are much harder to control. VAT, for example, is a direct tax only to the extent that poorer households differ in their spending from richer households.

The UK did a study in the early 2000s to show who was paying the most tax in relation to their income.

As we can see, the rich pay 43% of their income in taxes, while the poor pay 25% – 31%. But the poor pay more in direct taxes than the rich do.

-> We should always look at the tax system as a whole.

-> We should take into account the benefits people receive. The poorest households receive money from the state which then needs to be paid as tax back to the state.

Chapter 4: Taxation and the Economy

Taxation was so high in the Roman Empire that not doing anything was more profitable than doing any type of trade at some point.

Many developed countries have the same problem today. Let’s see the impact of taxation on the economy.

Taxation is the transfer of resources from taxpayers to the government. Three costs are created in the process.

- The cost of the tax system: the tax system isn’t free, you need to hire civil servants, accountants, etc. In the US, the cost is estimated at $40 per capita.

- The cost taxpayers incur to pay taxes: they have to spend time calculating how much they own, hire an accountant, etc. In the US, the cost is estimated at $250 per capita.

- Distortionary effects of taxes: all of the things people do because they have to pay taxes and that they wouldn’t do otherwise -> excess burden of taxation: it’s the additional cost that a tax has on society -> the cost of all taxes is higher than the taxes paid.

Efficiency in tax policy means minimizing the excess burden of taxation.

Eg:

- In 1696, England taxed people according to the number of windows their houses had. As a result, people started blocking their windows and suffered from the lack of sunlight, which cost society much more than not taxing windows in the first place.

- Fins go buy alcohol in Estonia because there are fewer taxes -> wasted time and energy spent on not paying taxes.

- Taxes on goods and services influence what and where people buy.

- Work taxes influence how much people work.

- Taxes on savings influence how much people save.

- Taxes on company profits influence where the company is based, how it is owned and financed, how much it invests, how much it produces, and how many people it employs.

This is what the economic cost of taxes is:

Eg: you want to hire a house decorator for no more than €1000. The cheapest you find charges €900 but needs to add 20% tax which makes €1080. Too expensive, you don’t hire the decorator -> taxes slow down the economy.

The higher the tax rate is, the higher the excess burden is – and it increases exponentially.

-> the best taxation is:

- Not too high

- Spread over different sectors

In the early 1930s the economist and mathematician Frank Ramsey (…) showed that a government (…) would minimize the overall excess burden by setting different rates of tax on different goods and services.

He showed that products whose demand and supply are impacted by taxes should have a lower tax rate than products that aren’t.

The only problem with such a theory was that it would complexify the levy of taxes.

The Case For Taxing Land

All taxes on things change the behavior of people when it comes to consuming those things (taxes make things more expensive, so fewer people buy when something gets taxed).

As a result, policymakers should seek to levy taxes without disturbing the market. Since the cost of taxing is exponential, states must spread these taxes over everything.

Two instruments though, have no distortionary costs: poll taxes, and land value taxes.

A poll tax does not influence behavior since…it’s something you pay regardless of what you do. But the problem with poll taxes is that they appear to be unfair (the rich pay the same as the poor).

The second is a land tax. Taxing land will not influence how much of the land you use since once you’re on it…you’re on it.

However, we don’t use this tax more because landowners are a powerful lobby, and because this would make the land drop in value.

Taxes and the Labor Market

The labor market is likely the one where tax policy has the greatest distortionary effect because:

- Taxes raised on employment are monstrous

- A huge part of these taxes is paid by the employee, which plays into his incentive to work.

When you tax labor, labor becomes expensive. Some jobs that could be profitable tax-free become unprofitable with a tax.

Studies showed that income tax only influences the decision to work for women with children and people over 50 years old.

Income tax policy has to face up to a sharp, and largely unavoidable, tradeoff between achieving distributional equity between rich and poor, and minimizing the efficiency costs of taxation, in terms of disincentive effects and other distortions to working behaviour.

Equity VS efficiency.

Metaphor: a leaking bucket. Income can be transferred from rich to poor with a bucket, but that bucket is leaking.

Maximum tolerable leak: 60% for every 1$ transferred.

Tax Wedges in the Labour Market

The tax wedge in the labor market is the difference between what the employer pays the employee and what the employee receives.

The tax drives apart the cost of the employer and the benefit of the employee.

Interaction Between Income Tax and Benefit Policies

Getting people to work low-income jobs isn’t only about not taxing their job – it’s also about not giving them too many benefits.

When an unemployed person gets a job, he goes from receiving money while not doing anything to paying taxes. Not only does he have to give a part of his salary (the income tax), but he also loses the benefits.

This is called the “participation tax”, the money he loses by getting a job -> people think twice before finding work.

In the UK, France, and Germany, the participation tax of low-wage workers is between 60% to 80%. We can decrease this tax by enabling workers to keep a part of the benefits they receive while working.

Chapter 5: Tax Evasion and Enforcement

States fix taxes, but they also ensure people pay them.

Tax evasion can be observed through three perspectives.

Individual Tax Evasion

Three factors play a role in how many people evade taxes.

- The flexibility of the tax system: when people get their taxes levied “at the source”, they can hardly evade them.

- Gain VS risk perception

- A mix of moral, psychological, and social pressure.

People get a chance to cheat when they declare themselves how much it is that they earned.

Eg: annual tax return.

Taxpayers can:

- Underdeclare

- Exaggerating business expenses or charity donations

- Hiding an entire activity (rare in modern countries)

Employees have it very difficult to evade taxes as their information can be cross-checked with their employer’s information.

This isn’t the case for self-employed people. Self-employed control everything, and how much they earn is always left to interpretation (Eg: business expenses).

Massive tax revenue is lost through tax lawsuits, tax avoidance, and aggressive tax strategy.

States don’t punish too much for tax avoidance as this would likely scare away people that already evade taxes a bit and would spur their moving out to other places.

So why do so many people do pay their taxes if the penalties and risks of getting caught are so low?

- These people are risk-averse

- People overestimate the risks involved in tax evasion

- Moral reasons

Tax Enforcement

The best way to avoid tax evasion is to get as many taxes retained at the source as possible.

A second way is to force people to report everything they paid to other people, so states can compare that with how much people declared.

In general, people do what other people are doing. If they think other people evade taxes, they will too.

Chapter 6: Issues in Tax Policy

Tax law is dangerous.

Changes in taxation have provoked revolts and rebellions throughout history, sometimes with dramatic consequences.

The US and Indian independence started with opposition to taxation.

What Makes Good Tax Policy?

Adam Smith answered this question in his book The Wealth of Nations. Tax policy needs to rest on four principles.

- Equity of contributions: People must contribute in proportion to their respective abilities.

- Certainty of tax liabilities: No arbitrary taxes, they must be fixed and clear.

- Convenience of payment: Taxes need to be paid at the best time and in the easiest manner for those who pay them.

- Minimization of costs: the cost of raising taxes must be minimized, as taxes cost in four ways:

- Salary of tax collectors and civil servants.

- Slow down or destroy industries when they’re too high.

- Penalties for tax evaders may ruin them and prevent them from ever paying taxes which will be a net loss for society.

- Harassment from tax collectors.

Smith doesn’t specify how to balance these principles and what to do when they contradict each other.

Unfortunately, tax policy is often implemented as a result of political pressures, not as a result of rationality.

‘Neutrality’ as a Guiding Principle for Tax Policy

Neutrality as a guiding principle for tax policy (…) is a maxim that tax revenues should be raised with the least possible disturbance to economic activity.

This also helps counter lobbying.

This principle means that similar activities (different industries, different saving methods, etc) should face similar taxation.

There are currently three key policy issues in modern tax policy.

- Tax simplification

- A single-rate income tax

- Exemption of taxes for basic goods

Tax Simplification

This is a seductive idea as it would enable people to understand the tax system and to not spend so much time filling up tax declarations.

However, most tax systems are complex because they’ve been trying to close loopholes.

A Flat-Rate Income Tax?

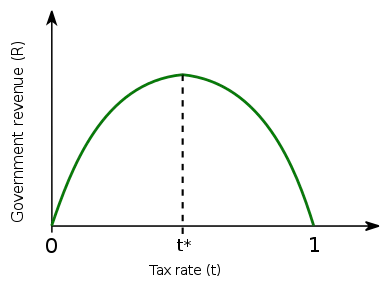

Some have said that the disincentive due to high personal income tax is so big that the state would levy more taxes if they decreased the income tax rate.

This is the Laffer curve. Above a certain tax rate (=t), people start evading taxes, not earning any money, moving out of the country, etc.

This is what the Baltic states have done by lowering taxes and establishing the same one for everyone.

It may seem that the lower income will have to contribute more than the higher income, but it wasn’t the case since they also gave a greater allowance for tax-free money.

Simulations of a similar flat tax rate in Germany have been made, and it has been found that it would considerably help the rich and “punish” the poor.

Sales Taxes and The Poor

Only Denmark applies a 25% VAT rate on everything. Other countries have different VAT rates for different goods and services (in the UK, it’s 0% for a lot of stuff).

However, the best system is the Danish system, as it is so simple that it minimizes the distortionary effect and excess burden.

Overall, differentiating VAT rates is not worth it. It’s better to have a high VAT and assist the poor by redistributing the money earned from VAT than having different VAT rates.

Tax Policy: the Future

Over the OECD area as a whole, tax revenues increased more than fourfold in real terms, as economic growth led to higher revenues, and more tax was raised through higher social contributions and the introduction of VAT.

The first force shaping tax policy is globalization and the fact that countries are now competing on tax.

People can now easily move from one place to another according to the tax policy applied -> countries lose fiscal sovereignty.

Highly redistributive policies will carry a significant cost in the form of outflows of highly skilled labour and capital, which will increase the cost of redistribution.

Unlike economic competition, fiscal competition isn’t benign. It enables big companies to shift profits to low-taxed jurisdictions which shifts the burden of taxation onto those who can’t afford to legally evade them.

The only way to avoid this is to create international agreements that limit countries’ capacities to be tax havens.

For more summaries, head to auresnotes.com.

Did you enjoy the summary? Get the book here!